-

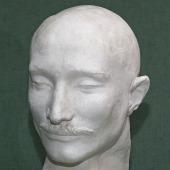

Plaster bust inscribed ‘Pierre-François Lacenaire’

-

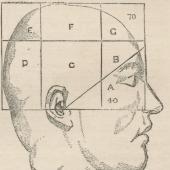

Model head to accompany the book Phrenology by L. N. Fowler

-

Frederick Bridges

Popular manual of phrenology -

Ambrose Lewis Vago (1839-96)

Orthodox phrenology -

John William Taylor

Noses and what they indicate -

George R. Sims (1847-1922)

How the poor live

What you see is what you get

Read all about it!

Can you spot a criminal among a group of people? One of the foundations of the nineteenth–century approach to crime was that there was a “criminal class” of people in society who were naturally inclined to commit crimes and could not be reformed. An extreme version of this approach was the opinion that criminal tendencies were actually inherited, that crime was the result of a genetic failing rather than a moral one.

The ‘science’ of phrenology studied the relationships between a person’s character and the shape of the skull. It was phenomenally popular in 19th century Britain as a form of popular entertainment similar to palmistry. Since different types of brain were thought to produce different types of skull shape: therefore by studying the skulls of known murderers one could identify the shape of head characteristic of a murderer. The model heads on display were used to accompany lectures as visual proof of the truth of the phrenological approach.

In Spain, phrenology, and the idea that skull shape could indicate presence or absence of criminal tendencies, was found within the growing sciences of criminology and psychiatry. The practice of photographing criminals – in this case bandits – was used by Julián Zugasti when he was sent as Governor to the province of Córdoba (in Andalucía) with the prime task of stamping out banditry in the area.