-

A compendium of knowledge (1)

-

A compendium of knowledge (2)

-

A compendium of knowledge (3)

-

A compendium of knowledge (4)

-

A compendium of knowledge (5)

-

A compendium of knowledge (6)

-

A compendium of knowledge (7)

-

A compendium of knowledge (8)

-

Imago mundi

-

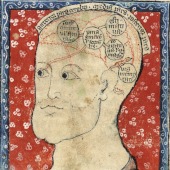

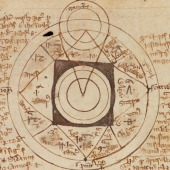

Medieval sciences (1)

-

Medieval sciences (2)

-

A case of double translation

-

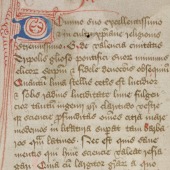

Precepts to an emperor

-

A choice of Anglo-Norman texts

-

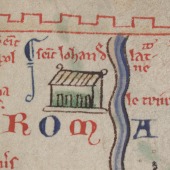

The route through Italy to the Holy Land (1)

-

The route through Italy to the Holy Land (2)

-

The route through Italy to the Holy Land (3)

-

The route through Italy to the Holy Land (4)

-

The route through Italy to the Holy Land (5)

-

The route through Italy to the Holy Land (6)

-

The route through Italy to the Holy Land (7)

Imagining the world: knowledge and science

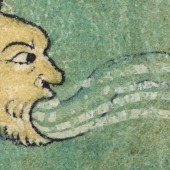

The moving word

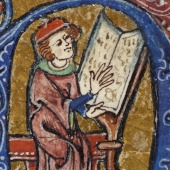

In the Middle Ages, scholars transmitted their knowledge of the world around them in a variety of forms, including geographical treatises, encyclopaedias, chronicles, commentaries, and literary texts. The manuscripts in this section of the exhibition testify to the multilingual learned cultures of the Middle Ages, an era in which students, scholars and texts flowed easily from one corner of the continent to the other, and especially to the major courts and centres of learning.

Teaching was organised around the seven liberal arts (grammar, logic, rhetoric, arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy) in medieval schools and was supplemented by geographical, medical, and alchemical (from the Arabic al-kimia, الكيمياء) texts which survive in both Latin and the vernacular.

Two items on display illustrate two major types of medieval geographical writing: theoretical and applied. The former is represented by the Image du monde (‘Image of the world’), an encyclopaedic text based on the twelfth-century Latin treatise, the Imago mundi. The second type of geographical writing is represented by itineraries, roughly the equivalent of guidebooks in the modern world. These schematic texts provided detailed descriptions of routes to be followed by the traveller (usually a pilgrim) and sites to be seen on the way to their destination. The fifteenth-century miscellany offers an interesting example of such an itinerary: beginning with the words Ki dritement veut aler en Jérusalem, primerement deit aler de Acre a Caïphas (‘He who wishes to go straight to Jerusalem, should first go from Acre to Kaifa’), the text details a number of important sites along the way.