Cambridge medieval libraries

The moving word

‘But, first, what are our means for pursuing such an investigation? We are best off if we have a catalogue.’ (M.R. James)

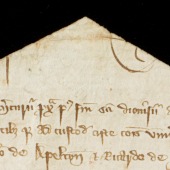

Catalogues and lists of books are our main source of information on medieval Cambridge collections, and amongst the earliest we find a 1363 indenture and several others from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. About 60 of these survive, covering 13 of the 15 colleges in existence at the time, as well as 75 wills in which donors bequeathed books to Cambridge institutions. This is an extraordinary body of information with few parallels in Britain or even in Europe.

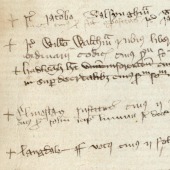

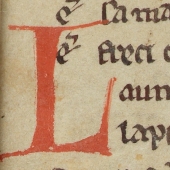

During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Cambridge collections grew rapidly and soon required a dedicated space. College and University statutes indicate the location of their new libraries, prescribe the hiring of a librarian and specify his duties, generally including the compilation of the library catalogue and its periodic updating. Catalogues normally aimed primarily just to conserve manuscripts; however, some catalogues, such as the one in Peterhouse’s Old Register (1418), are incredibly detailed and are in some ways the forerunners of later humanistic catalogues. Catalogues also had an important memorial function. Most collections grew not in response to precise development plans within the colleges but rather through the accumulation of occasional gifts. As Fellows and benefactors would often leave books to Cambridge institutions, naming and celebrating them was the best way to ensure future donations. Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, many of the catalogues list their items by benefactor. In some instances, the donation of books was also a part of the acts of foundation of the colleges.

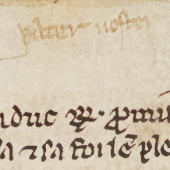

Cambridge libraries thus enjoyed a lively early history, in which the roles of the University and of the colleges were intertwined with scholarly, teaching and literary traditions. Manuscripts were acquired most often by chance before the era of purchasing based on need; they were ordered and managed differently, depending on the institution; and they even, on occasion, appear and disappear mysteriously from the catalogues. Donors, aware of human weakness, often explicitly indicated in their wills that their books should be chained in perpetuity within the institutional libraries.