Behind the Scenes

The Gutenberg Bible: an essay by Paul Needham

The Gutenberg Bible (better called Gutenberg-Fust Bible), the first large-scale production of the newly developed system of typographic printing, was completed in Mainz in 1455. Perhaps 180 copies were printed of this Latin Bible, available for purchase in either vellum copies (about a quarter of the edition run) or paper.

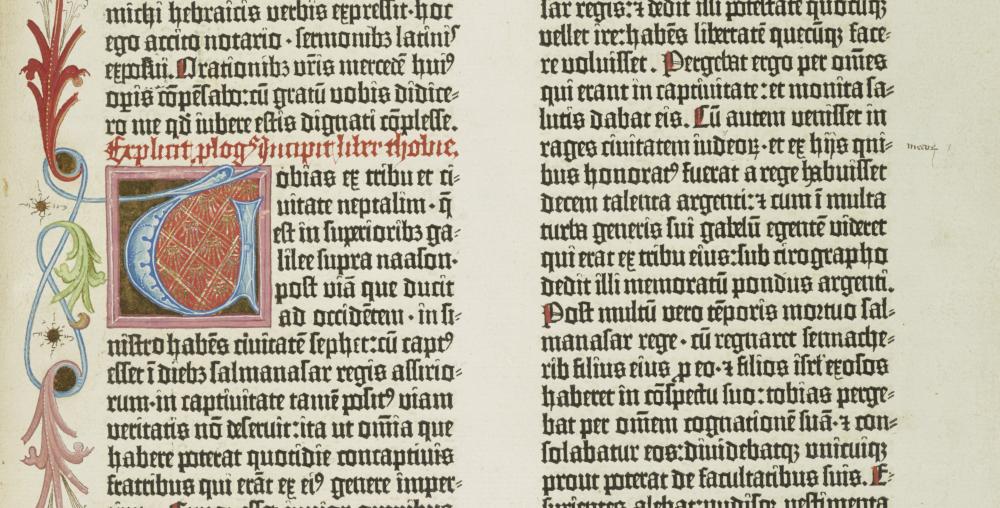

Each purchaser received the sheets of an intrinsically two-volume work in what is called Royal folio format, with leaf dimensions of roughly 40-41 cm in height and 29 cm in width: 324 leaves for the first volume, 319 for the second. Before they could be used, these Bible sheets had to be finished with hand rubrication supplying book, prologue and psalm tituli, initial letters, chapter numbers, and headlines; and then had to be bound. If purchasers wanted to pay extra they could further commission illuminated initials and borders. These features were typically supplied at the places where the various copies were sold, and not in the Mainz printing shop. The localizing features of illuminations and bindings, and various old ownership inscriptions, document that the Gutenberg Bible was sold widely outside the region of Mainz, with copies going to Southern Germany, Austria, Central Europe, Scandinavia, the Low Countries, and Spain. Because copies were sent to the Low Countries, it is not surprising that at least two copies, both printed on vellum, made their way across the North Sea to England. One is a beautiful copy now at Lambeth Palace Library, of which only the New Testament is preserved; the other vellum copy, illuminated in London, survives as a single leaf used as a binding wrapper, discovered in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century by John Bagford and now in the British Library.

The next surviving copy that we know to have reached the British Isles is that acquired, at an uncertain date in the early eighteenth century, by Charles Hope (1681-1742), first Earl of Hopetoun, and first resident of the grandly constructed Hopetoun House in Linlithgowshire. It is more rumor than established fact that the young Charles Hope, granted a peerage in 1704, bought rare books from the Jesuit college in Strasbourg. But there must be a kernel of truth, for a number of fine Hopetoun incunables have early Strasbourg provenances, especially of the old collegiate church, turned Protestant in the sixteenth century, of Saint-Pierre-le-jeune. When Hope acquired this Bible it would not have been thought of as the Gutenberg Bible, but only as an ancient printed Bible: as the spine labels put it, ‘BIBLIA LATINA EDIT. ANTIQ.’ The Hopetoun books descended to John Hope, seventh Earl and subsequently Marquess of Linlithgow. In February 1889, the year he sailed to Australia to assume the governorship of Victoria, Hope put the library’s rarities up for sale at Sotheby’s. Neither he nor anyone else had any idea that the family library included a Gutenberg Bible. Tom Hodge of Sotheby’s discovered it in a neglected cupboard as he was packing up the library for shipment to London. In the saleroom the Hopetoun Gutenberg Bible was bought by Bernard Quaritch, who in April featured it, with an unusually long description, in his Rough List no. 96, offering it at a modest markup of £250 above the hammer price of £2,000.

The purchaser was a Cambridge graduate, the London barrister Arthur William Young, who had matriculated at Trinity College in 1872. His family was well-off through its banking connections, and Young’s older brother Charles Edward Baring Young, likewise a Trinity graduate and for some years M.P., was prominent as a philanthropist, particularly to the poor youth of London. In 1911 Seymour De Ricci, in his census of copies of early Mainz printing, was clearly aware of Young’s ownership of the copy, but respected his wish for anonymity. Paul Schwenke’s Gutenberg Bible census, published posthumously, does name “A. W. Young, London” as the owner. The detail of the description suggests that Schwenke had either examined it or received a full account from its owner, and so we may suppose that Young gave permission for his name to be revealed in this place.

Forty-four years after his purchase of the Gutenberg Bible, in 1933, Young donated it to Cambridge University Library, together with many other printed books and medieval manuscripts from his small but valuable collection, which concentrated on the Bible. Among the manuscripts were five Wycliffite Bible manuscripts, representing both the earlier and revised versions. The incunable Bibles included a vellum copy of the 1462 Bible of Fust and Schöffer, of which the University Library held before this only a large fragment on paper; Schöffer’s 1472 Bible; four German Bibles, a Hebrew Bible, two French, a Dutch and an Italian Bible. Other significant incunables in Young’s gift are two of the three 1472-dated editions of Dante’s Commedia, and Caxton’s Golden Legend of 1483 which, though rather cut down, is one of a scant handful of textually complete copies. In sum, Young’s gift was the most important made to the University Library since 1714, when George I purchased for the university the massive library of John Moore, Bishop of Ely.

The interest of Cambridge’s Gutenberg Bible was magnified some fifty years after Young’s gift, when it was noticed that this copy had been carefully marked up and used as setting copy for the third of three Latin Bibles printed in Strasbourg by Heinrich Eggestein, and completed in late 1469 or early 1470. On every page of the Bible are small marginal hash-marks, pointing to unobtrusive vertical strokes within lines of the text, these strokes corresponding exactly, with a few indicative errors, to the page endings of Eggestein’s edition. Moreover, again in a small neat hand, there are in various books of the Bible (Luke, Acts, and a few others) marginal variant readings which Eggestein’s compositors introduced into their settings. In other words, the text of Eggestein’s third Vulgate Bible drew partially on a second, manuscript source. Presumably this hidden manuscript was also the source of variant readings in other books (1-2 Samuel, Minor Prophets, Psalms) that, although not entered marginally in the Gutenberg Bible, were nonetheless brought into Eggestein’s text, perhaps at a correction stage. These hundreds of small changes did not systematically improve on the Gutenberg Bible’s text, but they are the earliest example of editorial work on that text, and Eggestein apparently took pride in this. A printed broadside advertisement for his edition survives, in which he boasted that the edition had been ‘collated by men deep-dyed in humane letters’.

The discovery that the Hopetoun-Young copy of the Gutenberg Bible had been used as setting copy in a Strasbourg printing shop of the late 1460s brings us back to that unsubstantiated story of a Hopetoun purchase from the Jesuit College of Strasbourg. The Jesuit College was a late seventeenth-century establishment, and it is unlikely that its library would have had incunables and medieval manuscripts unless they had been brought there from some older, defunct religious house. Moreover, many of the Hopetoun incunables were fine Italian classical editions that could hardly have all made their way to Strasbourg by the early eighteenth century. Still, the Gutenberg Bible alone shows that at least one strand of the Hopetoun incunable collection led through Strasbourg. This Bible moved from its place of printing, Mainz, to Strasbourg and then remained there, unsold, for well over a decade. While in Strasbourg it underwent various stages of treatment and use. First (as the placement of the compositor marks and variant readings show), the major initials were illuminated in Strasbourg. Second, variant readings were neatly entered in a small hand in the margins of many pages. Third, the still unbound quires were separated into groups, and given out to at least four compositors in Eggestein’s shop to use as copy for their typesetting of a new edition. The compositors were presumably instructed to treat their copy with care and to keep it fresh, for the pages show little or no sign of having been handled apart from the small hash marks and vertical strokes. Fourth, probably in early 1470, after the compositors were done with their work (again as shown by the placements of the hash marks), the copy was carefully rubricated including the supply of all the initials which had not already been illuminated; bound; and sold. Where the copy remained for the next quarter-millennium before it ended up in Scotland cannot be known for sure, but by far the likeliest place is Strasbourg itself.

Essay by Paul Needham, Librarian at the Scheide Library, Princeton University.