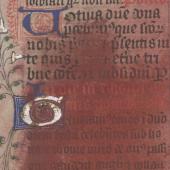

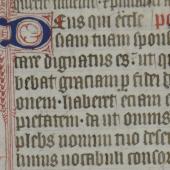

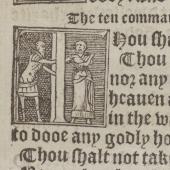

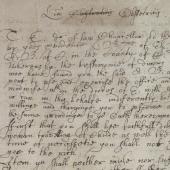

Ritual and Liturgy

Remembering the Reformation

Ritual lay at the heart of medieval Christianity. Attendance at Mass on Sundays was expected for all. While the laity did not regularly partake of the elements in communion, the apex of the rite was the elevation of the bread (the body of Christ) by the priest. This was a moment of sacred mystery. Members of guilds in larger churches would gather round the altar. Although it was difficult from other places to see, squint holes were placed in the rood-screen, and parishioners huddled to get a look. In the very largest churches, several Masses might be celebrated at the same time, staggered so as to allow a sermon to be heard at one while viewing the elevation at another. Gentry might hear Masses at different times in one day. Margaret Paston recalls her neighbour hearing three Masses one morning, coming home to his wife ‘never the merrier’; he then went to the garden for further devotion before taking his dinner. Hearing Mass was felt to bring many benefits, and not only succour for the soul: mothers in labour could expect safe delivery of their children, a traveller a safe return home. ‘Thy fote that day shall not thee fayll’, a song went. Mass was never more pressing than at death. Margery Kempe describes how the Corpus Christi guild in King’s Lynn ensured that the sacrament was carried through the streets during pestilence to help the dying to a final resting place.

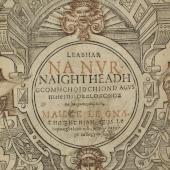

Early Protestants held such ceremonies in suspicion. The ritual actions of the priest in the Mass, holding the host aloft, kissing the book, smacked to them of superstition, and suggested that the Mass involved the changing of substances in the bread and wine, as if by magic. In the new liturgy, the Book of Common Prayer, prescribed in 1549 to replace the Latin services with Reformed ones in English, they endeavoured to remove as much ‘superstition’ as possible. The 1552 version was even more radical. For two hundred years, ritual remained at the heart of Reformation quarrels over religion. Yet in the midst of the doctrinal questions lurked a different problem of human memory. Individual lives stretched back before the changes, or lingered on into a new religious era. A priest ordained in the medieval church might not die until late in the reign of Elizabeth, by which time he would have seen four or five doctrinal régimes. Meanwhile his parishioners could recall one form of liturgy even as they experienced another. Surviving artefacts of the period, books as well as objects, bear these complex marks all over them.