Remembering the Dead

Remembering the Reformation

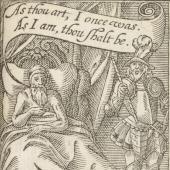

Attitudes to the dead were among the most fraught of all the religious conflicts of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The indulgence crisis in 1517 was itself concerned with the granting (and selling) of pardons to reduce the term in purgatory of a deceased relative. The dispute over sin and penance directly threatened traditional practices, which were also the source of strong emotional attachment. Medieval funerals for the dead combined many functions. This began before death, with the visitation of the sick, in which a crucifix was held in front of the dying person in a final opportunity for penance. While the priest made his way to the deathbed, the tolling of bells alerted the neighbourhood. After death, there were further rites; watching the body (the ‘wake’); making and reading the will; carrying the body to church. All of this preceded a mass for the dead (a ‘requiem’) combined with the litany, a vespers (or ‘Placebo’); and a matins and lauds combined (called ‘Dirige’).

These rites continued after the English Reformation until the institution of the vernacular Prayer Book in 1549. The new Order for Burial was then radically transformed from its elaborate medieval formation, and in 1552 was reduced to a minimum of ceremony. Purgatory was quickly abolished in the English Reformation, and tombs and charnel houses were desecrated; the dissolution of the monasteries involved the dispersal of dead as well as living inmates. However, remembering the dead continued, not surprisingly, to arouse strong feelings. Reformed funerals often went beyond the strict letter of the Prayer Book. Many local rituals survived the new theology. Bells continued to be tolled, and the corpse would often be met at the boundary of the church. Rites of passage between this world and the next were closely observed. As late as the 1650s, John Cosin, the future Bishop of Durham, exiled in Paris from Commonwealth England, was distressed when his son was denied a proper burial in Catholic France, crying out that he was forced to use little more ceremony than he would for his dog.