-

The destroyed shrine of St Thomas Becket

-

The first fruits of the new religion: iconoclasm

-

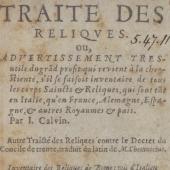

A satirical Calvinist inventory of Catholic relics

-

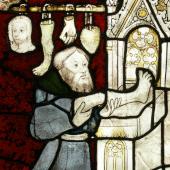

The popish past in glass

-

Remembering as resistance: a medieval primer reused in the recusant era

-

Recycling the sacred: the Stonyhurst Salt

-

The kiss of Judas: From ‘abominable idol’ to table of the Ten Commandments

-

Vox piscis: or, the book fish

-

‘An old popish Booke of homilies’: a Carthusian incunable

-

A Viking antiquity: the horn of Ulph

-

The finger bone of Miles Coverdale, bible translator

-

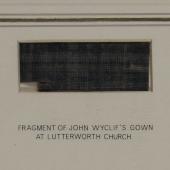

A fragment of John Wyclif’s gown

Casualties, Relics, and Survivals

Remembering the Reformation

In medieval Europe material objects played a vital part in the Christian culture of remembering. They reminded people of the key doctrines of the faith, of the lives of saints, and of the redeeming sacrifice of Jesus Christ himself. Understood as ‘the books of the laity’, images, statues, paintings, and stained glass windows were key features of ‘a complex indoor landscape of memory’. Their presence not merely recalled the piety of those who had bequeathed and endowed them; it was also a stimulus to intercessory prayer. Pilgrimages to relics and shrines brought the devout into physical proximity with hallowed remnants of the dead. Beyond the walls of parish churches, cathedrals and monasteries, wayside and market crosses provoked passers-by to remember the dead and recollect the Crucifixion, while holy wells, stones and trees kept alive the memory of the early missionaries who had first planted the faith.

The Protestant Reformation profoundly affected this rich culture of religious materiality. Designed to bring about the physical erasure of past error, the spasms of iconoclasm that punctuated its successive phases were both official and clandestine. Especially in regions where Calvinism took root, many ‘monuments’ of ‘superstition’ and ‘idolatry’ came under the axe and ended up on the bonfire. But not all vestiges of the Catholic past were destroyed. Some objects survived the tumultuous upheavals of the era, either because they were lovingly and daringly preserved by conservatives, or because they were recycled for alternative ecclesiastical or domestic purposes. Simultaneously, the very concept of relic itself was subtly changing: in the context of wider changes in historical scholarship and antiquarianism, some medieval items were reclassified as ‘antiquities’. Protestants themselves could not resist the human impulse to collect and keep remnants of revered religious figures. These became the elements of a new post-Reformation culture of material memory.