-

‘My chefest juel’: Edward VI’s copy of the Wycliffite bible

-

The lollard legacy: an heirloom bible

-

‘A bible used by Martin Luther 1522’

-

A Nuremberg notary’s Wittenberg bible

-

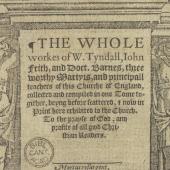

The monuments of the English martyrs

-

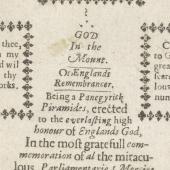

Paper monuments: England’s remembrancer

-

‘Jacob’s Stone erected in aeternal memorie’: remembering the Gunpowder Plot

-

A Protestant tobacco box: the smell of the Reformation?

-

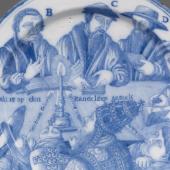

Commemorative tableware: a Dutch Delftware charger

-

The murder of Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey 1678: a memorial dagger

-

‘O bright example for the future age’: a funeral monument to Sir William Gee 1611

Monuments and Memorials

Remembering the Reformation

Monuments and memorials are features of every culture. In medieval Catholic theology, it was incumbent upon the living to pray for the dead and the plaques attached to memorial brasses and stone effigies often explicitly invited viewers to make such intercessions. This form of salvific remembering was sharply repudiated by Protestants, who violently condemned it as a species of heathen ‘idolatry’. But wholesale destruction of monuments to dead worthies and their families represented a symbolic threat to the social order that could not be sanctioned. In some places, their defacement or removal was expressly prohibited. The funeral monuments erected in the wake of the Reformation had a purely exemplary function.

In tandem with the advent of print and the spread of the Renaissance, the Reformation also stimulated new patterns of memorialisation. The humanist impulse to preserve textual and bibliographical vestiges of learned men helped to create vibrant cults of memory of Martin Luther and Philip Melanchthon, whose signatures and books were kept as memorabilia. Scribal copying and artistic embellishment of the works of famous reformers was itself a form of commemoration. More generally, following the precedent set in the Bible, Protestants created material memorials to give thanks for the providential deliverances of communities and nations, including the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot and Parliament’s victories over Charles I during the English Civil War. In time, the Reformation came to be regarded and depicted as an historic episode itself. Mechanical printing enabled the mass production of typographical ‘monuments’ made of paper and ink, which took the form of books and broadsides. Iconographies of Protestant memory spread from churches into domestic settings and left their imprint on portable objects as well as fixed schemes of interior decoration. The many and varied ways in which the words ‘monument’ and ‘memorial’ were used as both nouns and verbs are indicative of the vitality of the ‘arts of remembrance’ in early modern Europe.