-

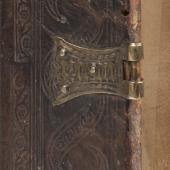

Black goatskin over wooden boards, late fifteenth century

-

Tanned calf over wooden boards, c. 1480

-

Citron goatskin, bound for Thomas Mahieu, c. 1550

-

Tanned calf over wooden boards, early sixteenth century

-

Sewn bookblock within limp parchment wrapper, late fifteenth century

-

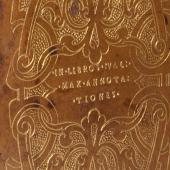

Alum-tawed pigskin over beechwood boards, possibly attributable to Konrad Dinckmut, c. 1480

-

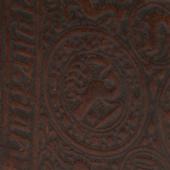

Tanned calf over wooden boards attributed to the Unicorn Binder, active c. 1478–1507

-

Pink-stained alum-tawed sheepskin over wooden boards, late fifteenth century

‘Neatly bound by its first owner in the earliest days of printing’

Private lives of print

The spread of printing across Europe in the fifteenth century led to a significant increase in demand for the services of bookbinders, and to changes in binding practices. Buyers of books in this period were offered a number of options. They could buy a text unbound, as loose sheets to be bespoke bound elsewhere, or they could buy a book folded and sewn, but otherwise uncovered. Alternatively, they could buy books sewn and bound in a simple paper binding, or in sheep, pig or calfskin, simply blind-tooled, or later more elaborately decorated with gold tooling.

Binding took place in a variety of locations and contexts. Printers bound their own books, along with books imported from elsewhere, and sold them directly from the printing house. Individual owners developed relationships with specific binders, who produced bespoke commissions. Monasteries frequently bound their own books, or had them bound by a local binder, in uniform style, whilst in university towns, binders produced cheaper bindings marketed for students and academics. Due to this wide variation, the study of a book’s binding can reveal much about the trade, movement, distribution and use of its contents.